Coral disease ‘firebreak’ works in short term. Next goal: Making it last

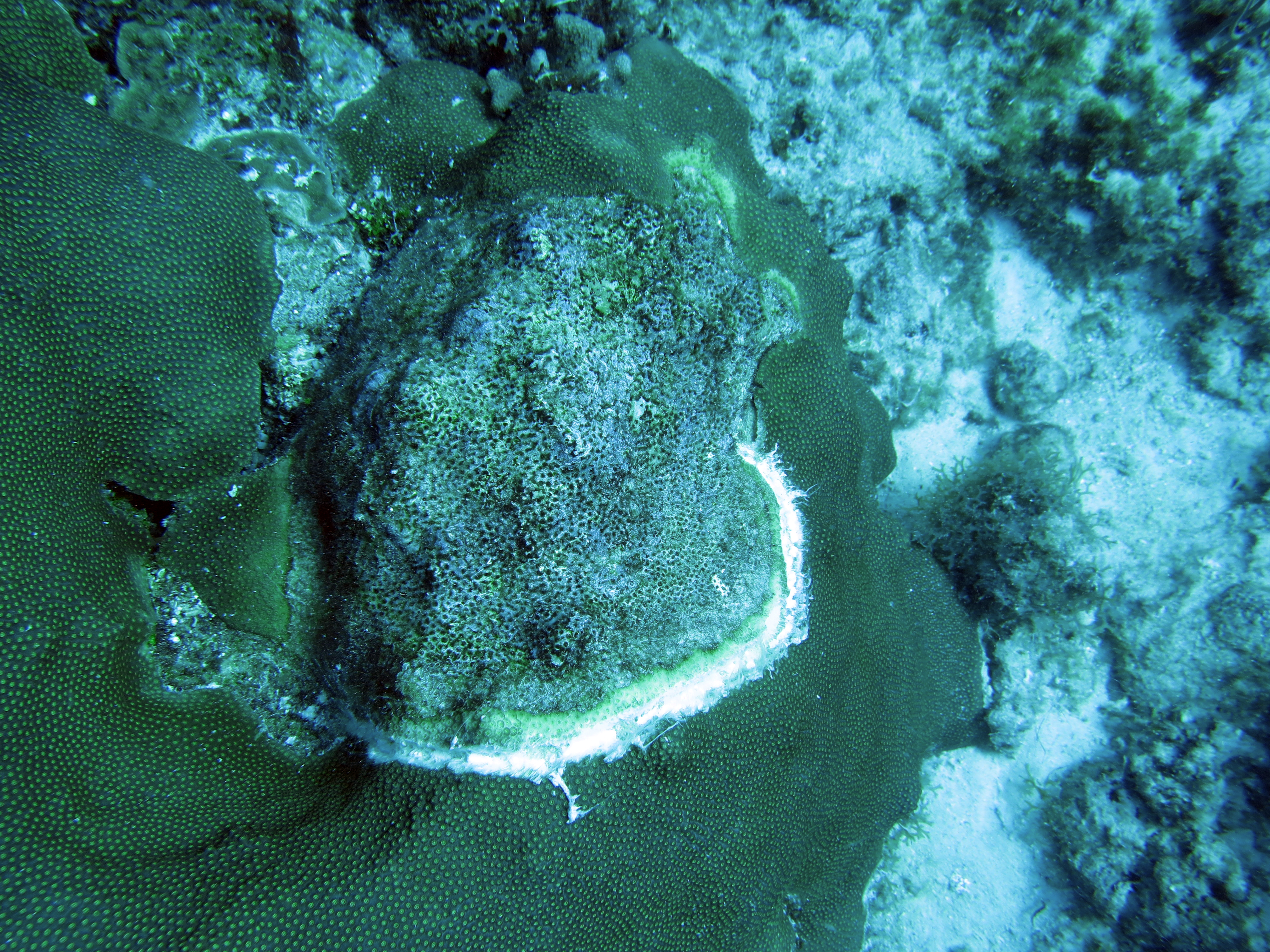

Mote Staff Scientist Dr. Erinn Muller chisels a firebreak around yellow-band coral disease. Credit: Dr. Carly Randall

The progression of Caribbean yellow-band disease — a widespread killer of reef-building corals — can be significantly impeded by chiseling a “firebreak” around the diseased coral tissue, but more research is needed to maintain the firebreak long-term, reports a peer-reviewed research paper published this week in the journal PeerJ.

First author Dr. Carly Randall of the Australian Institute of Marine Science worked on the study while earning her doctorate at Florida Institute of Technology, in partnership with Mote Marine Laboratory Staff Scientist Dr. Erinn Muller and scientists from the National Park Service in the study location: St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

The study site, Buck Island Reef National Monument, was designated to protect and preserve the coral reefs surrounding Buck Island. There, massive reef-builders such as the mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata) grow slowly over hundreds of years.

O. faveolata, listed as Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, is one significant victim of yellow-band disease, which has been present at Buck Island since at least 2005. Yellow-band progresses slowly relative to other coral diseases, but quickly enough to kill a large coral colony within a few years. Once a coral shows signs of the disease — healthy coral tissue fading into a blotch or band of pale yellow tissue-thinning, which spreads like a slow burn — recovery is rare. Even before a coral dies from yellow-band, its ability to sexually reproduce decreases.

“If we figure out a way to actually stop yellow-band, we can save that coral; if we can slow it down, then that could increase the reproductive output of the coral,” said Muller, Manager of Mote’s Coral Health & Disease Program and Science Director for Mote’s Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration on Summerland Key, Florida. “One good thing about studying yellow-band is that its relatively slow progression gives us time to figure things out.”

Effectively fighting coral disease is one “holy grail” for scientists and resource managers worldwide.

“Coral diseases are a real threat to coral reefs, and are expected to worsen as oceans warm, so we really need effective treatments to conserve what corals are left,” Randall said. “We are making headway in developing effective treatments, but more research is needed to identify the underlying causes of these diseases, so that we can tailor treatments to specific diseases.”

So far, studies suggest that yellow-band disease involves a group of Vibrio bacteria species that harm the corals’ “best buddies,” algae called zooxanthellae that give corals color and nutrition. Also, environmental stress such as high temperatures — expected more often with climate change — and the water-quality issue of excess nutrients can worsen yellow-band prevalence and spread.

Based on that knowledge and past studies of various disease treatments in other coral species, study partners tested three methods on wild O. faveolata at Buck Island: aspirating (vacuuming up and sterilizing) the diseased tissue with a machine, nailing a shade cloth to the coral to decrease stressful molecular changes from excess sunlight, and hand-chiseling a firebreak around the disease lesions to isolate them from healthy tissue.

“From the published literature, we don’t know of any other attempts to chisel a firebreak for Caribbean yellow-band disease,” Muller said. “However, the firebreak turned out to be the most effective method of the three, and in the short term it showed a lot of promise.”

First the team tried each technique with three infected colonies of O. faveolata apiece, starting in March 2015. In October 2015 they returned to take multiple photographs with measurement markers to detect disease spread. When preliminary results showed that only the chiseled firebreak method seemed to impede the disease spread significantly, the researchers found 30 more infected coral colonies to chisel. In total, researchers followed the original three chiseled colonies for 23 months, followed 19 chiseled colonies for 19 months and 11 for 16 months. Of all 33 colonies with chiseled firebreaks, 19 also had untreated disease bands serving as controls.

Left: Coral with chiseled "firebreak" around Caribbean yellow-band disease lesion. Credit: Dr. Carly Randall. Right: Carly Randall takes a measurement for a study of Caribbean yellow-band disease mitigation strategies in Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands. Credit: Dr. Erinn Muller/Mote Marine Laboratory

“One thing that is unique about this work is that we treated a large number of corals and tracked them for two years, which is a much longer period than most studies that have attempted to mitigate coral diseases,” Randall said. “But over the course of the study it became obvious that, due to the slow spread of the disease, we have to track Caribbean yellow-band disease for years to be confident in the results. While I’m confident in our results within the two-year timeframe, I’d like to track the corals even longer after treatment in the future.”

The researchers found that chiseled firebreaks reduced the rate and amount of tissue lost by 31 percent, and 30-40 percent of chiseled lesions appeared free of disease by 12-16 months. However, success significantly and steadily declined over 23 months. One reason: New coral tissue could regrow across the firebreak and reconnect with the diseased tissue.

“Initially I was a bit discouraged because what we thought was a very effective technique early on proved to have limited efficacy over the long-term,” Randall said. “But, we also have a good starting point to develop this treatment further, and I have hope that we can improve these methods to achieve a better outcome.”

Clayton Pollock, National Park Service (NPS) Biologist in the U.S. Virgin Islands who coordinated several aspects of this NPS-funded project, also expressed hope. “The results of this study are very encouraging and will guide the next steps of this ongoing research. I am hopeful that we can refine the methods and increase the efficacy of the mitigation. It is the mission of the National Park Service to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education and inspiration of this and future generations. Corals are the fundamental resource at Buck Island Reef National Monument, and corals are found in many of the coastal parks. Our research has conservation and management implications far beyond the boundaries of the park, and the National Park Service as an agency.”

Muller, Randall and Pollock each aim to undertake some key next steps.

“The next project, starting in 2019, will look at multiple coral species and multiple diseases with the firebreak process,” Muller said. “And I think we will incorporate an epoxy with an antiseptic along the firebreak, to enhance the barrier. We hope that the firebreak and the antiseptic will be a one-two punch.”

She continued: “In the recent study we were also limited by the effort it took to hand-chisel the firebreaks. For our work in 2019, we have purchased an underwater angle grinder that I hope will eliminate the need to chisel.” The angle grinder works like a larger version of a common rotary tool that can be used for polishing, cutting, or grinding.

“I am hopeful that we can refine the methods and increase the efficacy of this mitigation,” Pollock said. “In addition to incorporating epoxy with an antiseptic to enhance the firewall barrier, it will be important to collect and analyze genetic samples from the healthy and diseased colonies to see if certain genotypes are more resilient than others to diseases.”

While researchers strive to solve this challenge, how can the general public help corals?

“Any actions that help reduce stress on the coral at the local level have the potential to boost the coral’s capacity to fight off infection,” Randall said. “I would encourage the public to support local efforts to improve the health of their coastal communities. That might look like limiting pesticide use, picking-up your pets’ waste, and performing beach clean-ups. Ultimately though, reducing greenhouse gas emissions (such as carbon dioxide from transportation and other industries) is critical to combat the underlying cause of many coral diseases, which is a warming ocean.”