Cuba research to make splash on Discovery Channel’s Shark Week

From left: Mote scientists Dr. Robert Hueter and Dr. Kim Ritchie, and Cuban scientists Alexei Ruiz Abierno of University of Havana and Dr. Fabián Pina Amargós of Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research ride through a mangrove channel during the February 2015 expedition to study sharks and corals in Cuba. Credit Discovery Channel.

Shark and coral researchers from Mote Marine Laboratory are releasing results of a landmark expedition in Cuba — an international team effort that will be featured July 7 during Discovery Channel’s Shark Week.

The expedition allowed U.S. and Cuban scientists to place the first satellite transmitter tags on sharks in Cuban waters, conduct the first coral transplant experiment on a Cuban reef and more. Fieldwork took place in February 2015 and the satellite transmitters generated data afterward. Now the underwater action will be front-and-center in Discovery’s “Tiburones: The Sharks of Cuba” at 10 p.m. ET/PT on Tuesday, July 7.

Project partners hailed from Mote, a world-class marine research institution in Sarasota, Fla., from Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research, the University of Havana, and other Cuban institutions, and from the Environmental Defense Fund, which organizes U.S.-Cuban collaborations in science and conservation. Filmmakers from Tandem Stills + Motion, Inc. and Herzog Productions captured the action for Discovery. The Cuban production company Mundo Latino also filmed the expedition for a domestic television program in Cuba.

Click the image to watch a Discovery Channel video. Here, experts from Mote Marine Lab, Environmental Defense Fund and Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research talk about why we must study and preserve sharks and corals together. Credit Discovery Channel.

Cuba and the United States are fundamentally connected by the Gulf of Mexico and Straits of Florida. Animals such as sharks and other fishes, sea turtles and marine mammals migrate between the U.S. and Cuba, and both nations host coral reefs, “rainforests of the sea.”

Both nations also host significant marine protected areas and have important natural resources that need further scientific study to support management and conservation. However, Cuba — which has protected 20 percent of its coastal environment and has experienced slower coastal development than many other areas — stands out among the Gulf and Caribbean nations for its near-pristine ecosystems and wealth of unsolved scientific mysteries.

The Gulf and Caribbean ecoregion hosts about 20 percent of the world’s shark biodiversity, with Cuba at the epicenter, but scientists know relatively little about the status of shark populations in Cuban waters and what impacts they face from the nation’s fisheries. Over the past 40 years, the abundance of many shark species worldwide has declined dramatically. Rebuilding shark populations benefits the ecosystem and local economies because sharks are essential to the fishing industry and to ecotourism and are critical for proper ecological balance of life in the sea.

Many of Cuba’s coral reefs have thrived — with beautiful stands of elkhorn corals that are listed as threatened in the U.S. — even though most reefs in the Caribbean have declined. Science has yet to explain why reefs are healthier in Cuba and whether Cuban reefs exchange their drifting babies, or larvae, with reefs of other nations.

U.S. and Cuban scientists have sought to study sharks, corals and other marine fauna together, but they have needed to overcome the challenges of the multi-decade trade embargo that has severely restricted travel between the two nations. Recently, U.S.-Cuba diplomatic relations have improved — which may help increase the opportunities for Cuban and American scientists to collaborate on important scientific questions of mutual interest for both countries.

For more than 10 years, Mote scientists have been traveling to Cuba and forging collaborations with Cuban institutions, often with the vital assistance of EDF staff who have been developing local relationships in Cuba for more than 15 years. Mote is an independent, nonprofit institution not subject to as many Cuba travel restrictions placed on U.S. state and federal institutions. The Lab’s top-notch scientists have been working with Cuban partners to study the nation’s sharks and rays, other fishes, marine mammals and corals — and February’s expedition advanced their work in exciting ways.

“This expedition allowed U.S. and Cuban scientists to achieve some of the goals we’ve been dreaming about for years,” said Dr. Robert Hueter, Director of the Center for Shark Research at Mote Marine Laboratory. “For instance, we had been trying to get permission to deploy satellite tags on sharks in Cuba for at least five years, and we were finally given approval to do that on this expedition, thanks in large part to the great partnership with our Cuban colleagues and EDF. It all came together beautifully.”

“Trustful collaboration is the way to go if we want to preserve our shared resources,” said Cuban partner Dr. Jorge Angulo Valdes, Director of Conservation at the University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research. “This expedition showed how much we can accomplish together.”

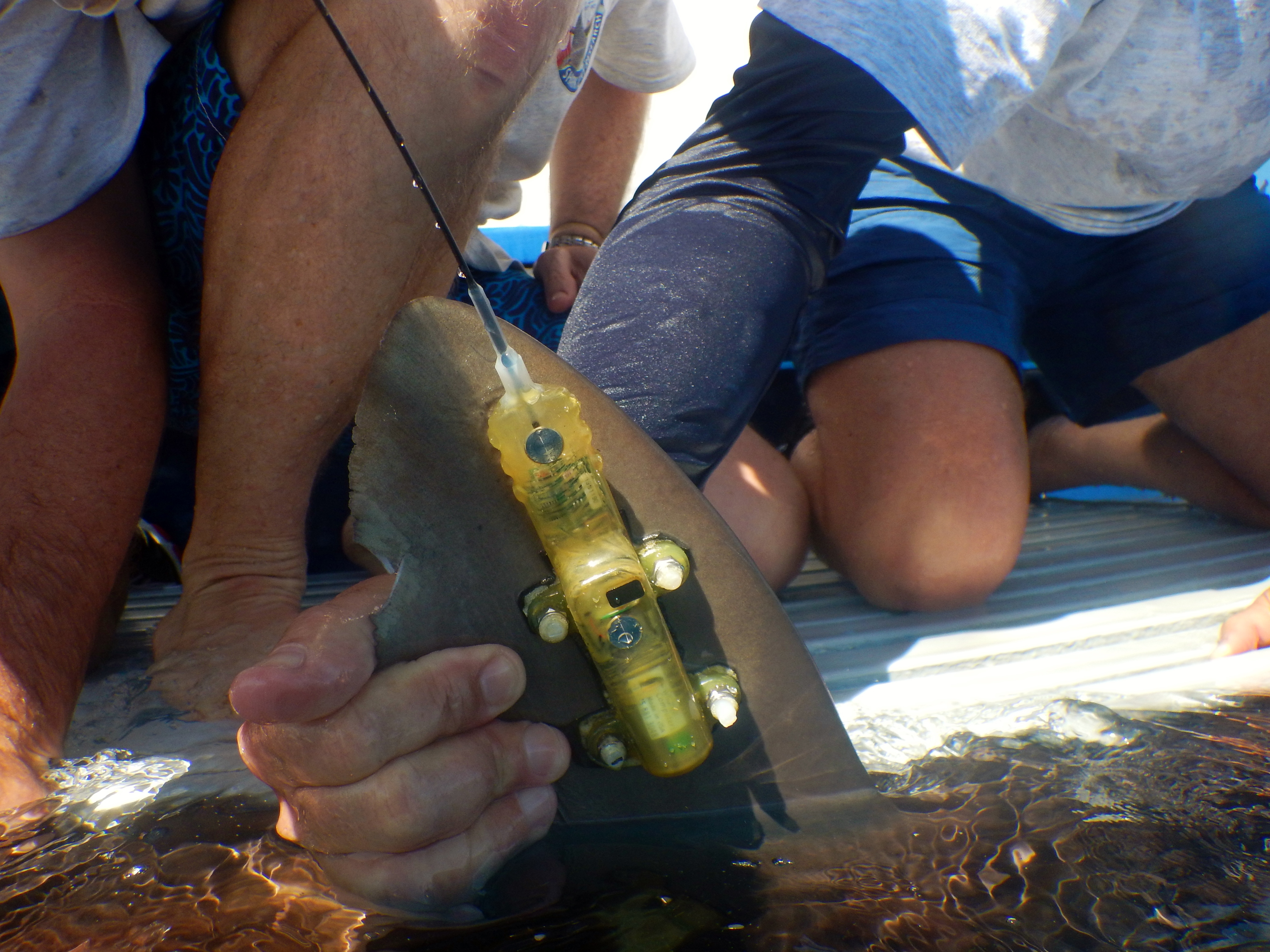

A silky shark's dorsal fin is fitted with a satellite transmitter during the February 2015 expedition, the first-ever expedition where sharks were satellite tagged in Cuban waters. Credit Mote Marine Lab.

Key outcomes for shark research from the February 2015 expedition

- The team placed the first satellite transmitter tags on sharks in Cuban waters. Satellite tags allow scientists to know where sharks travel to better understand their life histories, habitat use and vulnerability to fisheries. Three silky sharks were fitted with satellite tags in the Jardines de la Reina (Gardens of the Queen) National Marine Park off of Cuba’s south coast. One shark is wearing a real-time transmitter that sends periodic signals, and the researchers are monitoring its geographic movements. The other two silky sharks were outfitted with tags designed to pop up and send data to the Mote scientists. Just over a month later, the tags revealed that the sharks had made movements away from the inshore reef area where they were tagged and into deeper offshore waters, spending most of their time in the upper water column but also diving during the day. One of the sharks reached a maximum depth of 2,073 feet (632 meters). This reveals these sharks don’t just spend their time on the reef but occupy very deep water offshore as well.

- The team also deployed a pop-up satellite tag on a very rare longfin mako shark off Cuba’s north coast. The tag is expected to pop up, float to the surface and send data to the scientists in mid-July. This was one of just a few longfin makos satellite-tagged in the world, and another was Mote in the U.S. portion of the Gulf of Mexico.

- For the first time, large sharks were fitted with satellite tags using no hooks, nets, ropes or spears. Instead, a Cuban divemaster used a special calming technique that involved applying gentle pressure to each shark’s tail fin as it swam freely, until the shark relaxed and was cradled in the divemaster’s arms. The calming effect is similar to the method of “tonic immobility,” in which sharks are turned upside down, and the research team nicknamed the Cuban’s technique the “fin & tonic” method. (Remember: Don’t try this at home! Sharks are wild animals and the public should give them space.)

- The researchers also tagged a young lemon shark and young nurse shark in mangrove habitats, showing the value of these areas as shark nurseries.

- The team located and interviewed a man who was present in the 1945 landing of “El Monstruo de Cojimar” (the Monster of Cojimar), a 21-foot great white shark believed to be the largest reliably measured white shark on record anywhere in the world. The man recounted the details of the catch for the scientific team and production crew, confirming the anecdotes about this famous shark record.

These successes are early but vital steps toward filling information gaps about shark populations throughout the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. “These important accomplishments represent a quantum leap forward in our U.S.-Cuba collaborative studies of sharks that began about ten years ago,” Hueter said.

“Across the Gulf of Mexico region, our long term aim is that improved international cooperation, science, and management and the exchange of expertise will lead to the recovery and long term health of shark populations,” said Daniel Whittle, Cuba Program director for EDF. “Sharks have been around for 400 million years. We don’t want them to disappear on our watch.”

He noted that Cuba is poised to develop its first national plan of action for sharks — an effort that is drawing upon the expertise of Cuban scientists, EDF staff and Mote’s Center for Shark Research.

February’s expedition also focused on the spectacular coral reefs in the Gardens of the Queen sanctuary.

“It’s incredible,” said Dr. Kim Ritchie, Manager of the Marine Microbiology Program at Mote. “There are big, beautiful big stands of elkhorn coral as far as the eye can see, and schools of fish we’re not used to seeing in the Florida Keys.”

Ritchie said there’s a lot to learn about Cuba’s reefs. Elsewhere in the Caribbean, scientists have documented the “genetic fingerprint” of elkhorn corals to understand which corals are related and where their larvae might have started life before settling to grow into adult corals. But in Cuba the genetics of corals remain largely unstudied, and so do the microbes that can significantly influence coral health.

February’s expedition laid groundwork for those types of research and more.

Dr. David Vaughan of Mote Marine Laboratory transplants small pieces of elkhorn coral from a healthy reef area to a depleted area in Cuban waters, carrying out the first-ever coral transplant experiment in Cuba during the February 2015 research expedition with Cuban and U.S. scientists. Credit Mote Marine Lab.

Key outcomes for coral research from the February 2015 expedition

- In the Gardens of the Queen, the researchers conducted the first coral transplant experiment in Cuban waters by attaching healthy elkhorn coral fragments to dead coral skeletons to see if they can restore new coral growth to a depleted reef. To observe the results, a return trip to the site is planned.

- “The Gardens of the Queen has an area with unbelievably pristine elkhorn coral heads like I remember seeing in Florida and the Caribbean during the 60s, and it also has a desolate stand that looks like it had perished from bleaching, disease or storms,” said Dr. Dave Vaughan, Manager of Mote’s Coral Restoration Program, who worked with Cuban partners on the coral transplant.

“We were able to find a piece of coral that had broken off in the good area and transplant it in many small pieces to an area in the desolate stand to see if the drastic difference between the two areas was caused by location or genetics. This will tell us if these healthy corals have special resilience to stressors like disease or if perhaps they’re in the right location to be less affected by storms. Coral transplant studies are vital for informing reef restoration efforts in Cuba, Florida and the Caribbean.”

- The team also shared coral survey and sampling methods with the hope of one day partnering to generate some of the first genetic and microbiological data to help better understand these resilient corals. This expedition was key to laying groundwork for the future of U.S.-Cuba coral research, in the hopes that more open scientific exchange between the nations will become possible.

Research partners in the February 2015 expedition included:

U.S.

Mote Marine Laboratory:

Dr. Robert Hueter, Director of Mote's Center for Shark Research

Dr. Kim Ritchie, Manager of Mote's Marine Micriobiology Program

Dr. Dave Vaughan, Manager of Mote’s Coral Restoration Program

Jack Morris, Senior Biologist

John Tyminski, Associate Researcher

Environmental Defense Fund:

Dr. Douglas Rader, Chief Ocean Scientist

Daniel Whittle, Director of the Cuba Program

Cuba

Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research (Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros, CIEC):

Dr. Fabián Pina Amargós

Tamara Figueredo Martin

University of Havana, Center for Marine Research:

Dr. Jorge Angulo Valdes, Director of Conservation at the University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research

Alexei Ruiz Abierno

Lazaro V. Garcia Lopez

National Center for Protected Areas (Centro de Nacional de Areas Protegidas, CNAP):

Susana Perera

Ministry of Food, Office of Fisheries Regulation and Science

Raidel Borroto

Other partners:

U.S. film producers

Ian Shive, Tandem Stills + Motion, Inc.

Chris Cowen, Katie King and crew, Herzog Productions

Avalon Dive Center, Cuba

Noel Lopez Fernandez

Mundo Latino, Cuba