Coral Reef Restoration

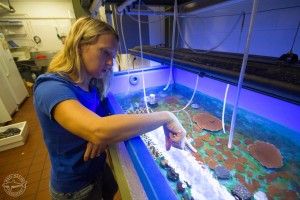

Seeking to develop systems and techniques to grow coral and other reef species.

1600 Ken Thompson Parkway

Sarasota, FL 34236

Ph: (941) 388-4441

Hours: 10AM - 5PM

A 501(c)3 nonprofit organization.

----------

----------

Dead, white coral skeletons litter once-beautiful areas of Florida’s reef tract, the world's third largest shallow-water, barrier reef system. Most of the reef is bare, with no living coral in sight — reminiscent of a post-apocalyptic film scene. Now, Mote Marine Laboratory scientists and partners are pursuing the deadly culprit, coral tissue-loss disease, which is causing what is now known as one of the longest and largest infectious coral disease outbreaks in recent history.

The disease is believed to have originated off Virginia Key in Miami-Dade County in fall 2014 and began spreading quickly north, south and west, with the mortality rate as high as 100 percent in some coral species. The disease now reaches as far north as the northern most sections of the Florida reef tract in Martin County and at least as far south as Looe Key in the Lower Keys.

In April 2018, Mote scientists first learned of the disease in Looe Key and, with collaborators from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), visited the iconic reef site to remove the few diseased corals to minimize the outbreak, but found that the outbreak was more significant than expected.

“We knew there was a disease occurring, but it’s difficult to comprehend how fast this disease progresses until you see it first-hand,” said Erinn Muller, Manager of Mote’s Coral Health & Disease Program and Science Director of Mote’s Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research and Restoration (IC2R3). “What is also surprising is the number of species affected. To date, 22 species have been affected, all with varying degrees of susceptibility, rates of progression and mortality.”

As of early July 2018, more than half of Florida’s reef tract has been affected – exceeding 96,000 acres.

While coral disease outbreaks are not unprecedented, this event is unique due to its large geographic range, extended duration, high rates of mortality and the number of species affected.

Scientists believe the cause of the disease is likely a bacterial infection carried by water currents and touch, but this has not been confirmed.

“Many factors often contribute to coral disease, so the exact cause of any outbreak is difficult to determine," said Muller. "In this case, it is possible that local threats such as sedimentation and land-based sources of pollution, perhaps in combination with unusually warm water temperatures in recent years, weakened the corals’ resilience, allowing naturally-occurring viruses, bacteria and other microorganisms to become more lethal. However, this could also be a completely novel pathogen.”

Scientists brought a few samples from their April assessment trip back to Keys Marine Laboratory to be divided among partner institutions for research. A Mote scientist brought samples back to Mote’s Sarasota campus for study, to avoid any potential contamination of corals being grown at IC2R3 on Summerland Key.

These corals were used to test for genetic resilience to the mysterious tissue-loss disease within corals used for restoration. Initial experiments showed that direct contact was needed for transmission to occur and that some genotypes may be more susceptible than others.

While the exact cause of the disease may never be known, Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and numerous partners from federal, state and local governments, universities, non-governmental organizations including Mote, and the South Florida community have been communicating regularly and working together on a multi-faceted response effort. The effort includes: disease surveys and monitoring; strategic sampling and laboratory analysis to find potential causes; data analyses to determine what may influence the disease progression; and identification of potential management options to mitigate disease impacts, assess the effectiveness of treatment techniques and prevent the further spread of disease.

“While the tissue loss disease outbreak is unprecedented, so is the collaborative response to it,” Muller said. “It is truly amazing and impactful to see all these organizations coming together for one cause – to better our coral reefs.”

Mote scientists are leading multiple aspects of the research on the disease.

In the ocean, Mote scientists are studying where, when and how the disease is spreading. They are collecting samples from the leading edge of the outbreak to test for disease resistance in massive coral species that are used for reef restoration.

In recent years, Mote alone has planted 45,000 corals with plans to plant 25,000 more this year. Muller and her team are also studying non-diseased coral fragments grown at IC2R3 to determine their resistance and/or resilience to the tissue-loss disease for future outplanting.

“The tissue-loss disease outbreak is a grand challenge to Florida Keys coral reefs, and its seriousness cannot be overstated, but Mote is working tirelessly to advance resilience-based restoration efforts to bring depleted reef areas back to life,” said Michael P. Crosby, Mote President and CEO. “Mote was intensively advancing coral reef science and restoration years before this outbreak. As a result, we are ideally prepared and dedicated to applying what we have learned, strategically, while continuing to advance our knowledge and efficacy.”

However, it will take time before this case is closed.

Mote is currently raising multiple genetic varieties of multiple reef-building coral species from Florida Keys environments — totaling some 38,000 individual micro-fragments of coral — in its nursery and gene bank at IC2R3 on Summerland Key. In the lab, Mote has tested the disease resistance and resilience of multiple genetic varieties, exposing them to infected material from the tissue-loss disease outbreak.

So far, Mote scientists have only been able to transmit the tissue-loss disease through directly touching a diseased coral to a restoration coral, and some genotypes appear more resistant to the disease than others — with disease resistance potentially “hard-wired” in their genetics, which Mote is examining to learn more. Mote scientists are working hard to expand on this finding in the lab and out in the ocean. Some of the genetic varieties Mote tested in the lab have already been outplanted in the ocean and lived for three years without succumbing to other kinds of diseases or other stressors such as heat-driven bleaching.

With this hopeful sign in mind, Mote has outlined and seeks to fully implement a 10-year, multi-institution, coral disease response & restoration initiative, which includes propagating and restoring as many as 50,000 coral “seedlings” to Florida Keys reefs each year, with a goal of increasing the living coral cover in the Florida Keys by 25 percent over the next 10 years, developing critical scientific infrastructure including inland coral gene banks and a disease research “clean room” for effective research to understand the disease without contaminating healthy corals, and establishing increasingly rigorous scientific assessments to ensure restoration practices succeed.

Pending the attainment of full funding support, scientists at Mote’s IC2R3, along with state and federal agency partners, local community-based non-profits and university colleagues, will be able to implement this 10-year initiative building on Mote’s novel and successful, genetic resilience-based coral restoration technology. Many years of research will finally be transformed into real action to bring the “rainforests of the sea” back from the brink of extinction.

Mote Aquarium is likely to be busy this week, with many timed-ticket entry slots selling out. Please purchase your tickets in advance to guarantee entry.

Mote Aquarium is open seven days a week at our normal hours, 9:30 a.m.–5 p.m. We hope to SEA you soon!