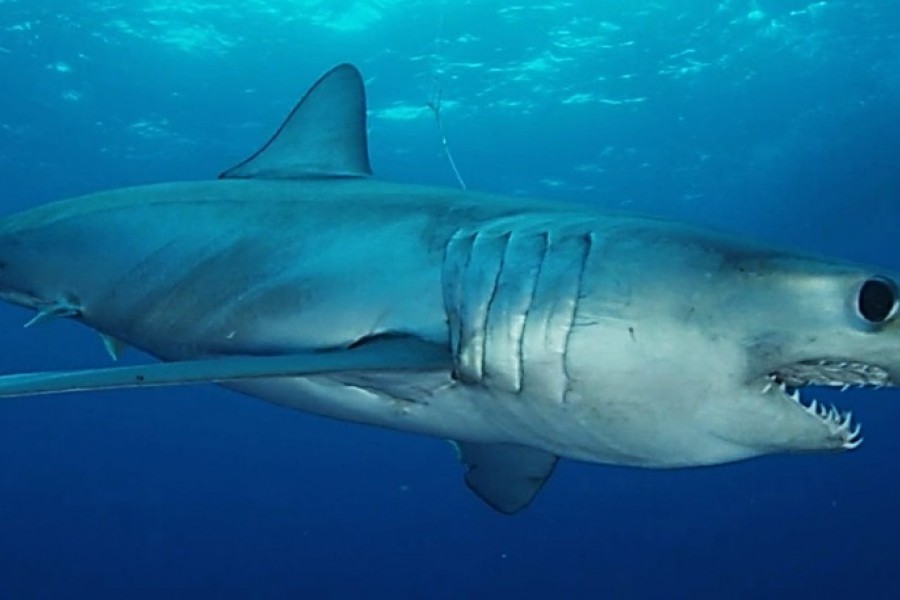

Tuesday Dec. 21, Mote Marine Laboratory scientists together with scientists from the University of Havana published the first-ever peer-reviewed scientific paper on the movements and habitat use of the longfin mako, a rare and vulnerable species of shark.

The study is based on two longfin makos tagged with satellite-linked tracking devices, one in 2012 and the other in 2015. The sharks’ movements shed light on the life of a rare species while demonstrating an important point: The U.S., Cuba, Mexico and the Bahamas are fundamentally connected by the sea.

Although rare, longfin makos are widely distributed in temperate and tropical waters around the world. This species generally inhabits deeper waters and is less well-known than its shallower-water cousin, the shortfin mako. Because of this lack of data and this shark’s low reproductive output plus its vulnerability to commercial longline fisheries, the longfin mako is a species of special conservation concern.

To find out more about the longfin mako, Mote and University of Havana scientists collaborated on the first study to use satellite tracking as a means of assessing the behavior, ecology and potential fisheries impact of this species.

“One of the important things we were looking for is the overlap in range between these two satellite-tagged sharks, to identify critical areas of habitat for this species,” said Mote’s Dr. Robert Hueter, the study’s lead scientist.

“This paper contains irrefutable evidence of how our two countries are connected, and how collaboration is the way to go to protect our common resources,” said Dr. Jorge Angulo Valdes of the University of Havana and University of Florida.

The first shark was tagged with a pop-up satellite tag April 27, 2012, during an expedition in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on the RV Weatherbird II of the Florida Institute of Oceanography. The tag detached after 90 days on the shark and transmitted a summary of its archived data from a location about 200 miles east-northeast of Virginia Beach, Virginia. The data showed the shark had stayed just off the continental shelf in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, moving in a southeasterly direction for the first three weeks.

It then had entered the Straits of Florida and continued on an easterly path between Cuba and the Florida Keys, passing into the waters of the Bahamas to the west of Grand Bahama Island. The shark then moved into the open Atlantic Ocean in early June, ending up off the Chesapeake Bay in July, when the tag popped off the shark and came to the surface. The total track covered nearly 4,231 miles in three months, averaging about 46 miles per day.

The second shark was tagged almost three years later on February14, 2015, offshore from the fishing village of Cojimar in northern Cuba, during an expedition by scientists from Mote, the University of Havana, Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research, and other Cuban institutions, and from the Environmental Defense Fund, which works with Mote to facilitate U.S.-Cuban collaborations in marine science and conservation.

After being tagged in mid-February, the shark departed from waters off northern Cuba, traveled with the Gulf Stream current between Florida and the Bahamas, and then doubled back into the eastern Gulf of Mexico, where it swam in a clockwise loop in April and early May between Florida and Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Then in May the shark swam back along the Gulf Stream, through the northern Bahamas and into deep waters of the open Atlantic, where it proceeded north until it was offshore of New Jersey in late June. Finally, it headed south to waters off Virginia, and its tag popped off and surfaced about 125 miles east of the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The total track covered nearly 5,500 miles in five months, averaging about 36.5 miles per day.

“What is most exciting about these results is that these sharks, both adult males, converged on the same spot off the U.S. east coast in the month of July, indicating this to be a summer feeding ground and possibly an area where these sharks are mating,” Hueter said.

The tag also showed the second mako spent a majority of its time in depths of less than 1,640 feet (500 meters), staying mostly deeper during the day than at night.

“The data from these animals indicated that longfin makos adjust their vertical movements in response to similar movements of their prey, such as squid,” said John Tyminski, Senior Biologist and co-author of the study.

The second mako made some extreme dives including one to 5,797 feet (1,767 meters), more than a mile deep. “At that depth the shark is dealing with extreme cold, close to freezing,” Hueter said. “The data from this tag will help us understand why these sharks are diving so deep and how they are dealing with such cold temperatures.”

Landing longfin makos in the U.S. is prohibited but they are caught as bycatch in pelagic (offshore) longline fisheries for other species, such as swordfish and tunas. The tracks from the two sharks showed that during their treks they did not spend much time inside areas protected from pelagic longlining on the U.S. east coast, meaning these closures may not be benefiting this particular species.

In some fisheries elsewhere, fins of this species are of desirable quality and have been reported in Hong Kong, Chilean and Indonesian fin trades. Its fins are also used in shark fin soup, a delicacy in the Asian culture.

“The most important thing we learned during this study is that these sharks go back and forth among the territorial seas of multiple nations, which shows the importance of coordinating our shark fisheries sustainability and conservation efforts on a multilateral, even global, scale,” Hueter said.