Since the early days of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which began April 20, 2010, Mote Marine Laboratory has played a significant role in research investigating how oil exposure can affect marine life during and even after a spill. Today, Mote scientists are working toward developing rapid health-diagnostic tests based on sub-lethal responses that will better predict short- and long-term impacts of oil exposure in Gulf of Mexico fishes.

Mote and partners presented preliminary research results at the 2016 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science Conference during Feb. 1-4 in Tampa, Florida. Those results helped lay groundwork for large-scale fish studies that Mote began this month, April 2016.

Mote and its collaborators are examining how specific levels of oil components affect fish under highly controlled conditions in the lab. These lab studies rigorously examine oil-related changes in immune and reproductive health, viability of offspring and other traits important for maintaining Gulf fish populations; lab results provide important baseline data to better interpret and help “decode” research findings from wild fish sampled during and after the spill. Together, lab and field studies aim to provide a head start in understanding threats to the health of Gulf fisheries for decades to come.

“With humans, our health is monitored from birth by our doctor, so later in life we know our medical history and what has changed,” said Dr. Dana Wetzel, manager of Mote’s Environmental Laboratory for Forensics. “We don’t have that luxury for fish in the Gulf of Mexico. We need to be able to look closely at how oil affects these animals, in a controlled setting, to better understand what we’re seeing now and to better prepare for the future.”

Wetzel is Toxicology Task Lead in the Deepwater Horizon research consortium called CIMAGE II (and its predecessor, C-IMAGE), which is based at the University of South Florida and funded by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. She and Dr. Kevan Main, a fellow senior scientist at Mote, are leading oil spill studies at Mote Aquaculture Park, the Lab’s sustainable fish-farming research facility. Wetzel was one of the investigators working on fish toxicology assessments within the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA)* coordinated by multiple federal and Gulf-state trustees. Mote, an independent research institution, is glad to contribute its cutting-edge studies to this major, long-term effort to understand and address the harm caused by the spill.

Preliminary results: effects on young fishes in the lab

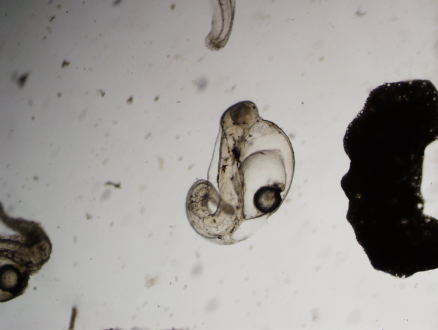

Left: A healthy red drum embryo; right: a deformed red drum embryo. Mote scientists presented preliminary results in February from a study in collaboration with NOAA and Abt Associates on how oil, dispersant and their combination affect the health of two species of young fishes. In this study, oil-dispersant mixture was more toxic than oil or dispersant alone. (Credit: Mote Marine Laboratory)

During the February conference in Tampa, Mote scientists presented results from a lab study performed in collaboration with NOAA and Abt Associates on how oil, dispersant and their combination affect the health of certain young fishes. This study contributed data to the broader NRDA, and its results may be further interpreted in context of other NRDA work.

The study investigated how weathered Deepwater Horizon oil, which degrades in the environment, affected the vulnerable early-life stages of red drum/redfish (Sciaenops) and other fish known as inland silversides (Menidia). Red drum represent estuary and bay habitats such as those affected or potentially affected by the spill, and inland silversides are fish commonly used as a test species in toxicity studies to allow cross-comparison with other research efforts.

The researchers exposed these early-life fishes to a range of concentrations of oil and dispersant, some that were lower and some that were greater than most wild fishes were likely to encounter from Deepwater Horizon. This allowed the team to monitor for clear and pronounced effects on fish health and collect controlled, baseline data so future studies can delve into the subtleties of lower-level exposures more representative of what fish encountered in the wild.

Results show that, in general, both fish species exhibited increased mortality and red drum embryos were more likely to be deformed with increased concentrations of dissolved oil. For both species, the oil-dispersant mixture was by far the most toxic — sometimes by an order of magnitude — than oil or dispersant alone. Other recent lab studies by various institutions — with microscopic organisms called rotifers and nematodes, spotted sea trout larvae, mustard hill coral larvae, mountainous star coral larvae, thinlip mullet and trout — have generally echoed the finding that oil and dispersant do more harm together. This is because oil becomes more soluble in water — and more available to the bodies of animals — when a surfactant (such as Corexit 9500) is added.

Mote Aquaculture Park: fish research scaling up this year

In 2015, Mote carried out oil-exposure studies with Gulf fish species at Mote Aquaculture Park, setting the stage for larger experiments getting under way now, April 2016. Left: A red drum in the research system at Mote Aquaculture Park. Right: Mote senior scientist Dr. Dana Wetzel works in the lab space at Mote Aquaculture Park. (Credit Mote Marine Laboratory)

In 2015, Mote carried out oil-exposure studies with Gulf fish species at Mote Aquaculture Park, setting the stage for larger experiments getting under way now, April 2016. Left: A red drum in the research system at Mote Aquaculture Park. Right: Mote senior scientist Dr. Dana Wetzel works in the lab space at Mote Aquaculture Park. (Credit Mote Marine Laboratory)

In 2015, Mote scientists carried out the first of several oil-exposure studies at Mote Aquaculture Park (MAP) with three important Gulf of Mexico marine fishes — red drum, pompano and southern flounder. These studies are helping to rigorously document specific ways that oil can affect immune and reproductive health, viability of offspring and other traits important for maintaining fish populations.

Starting in summer 2015, two fish-exposure studies were carried out at MAP using either Deepwater Horizon oil or South Louisiana Crude oil. The first study involved injecting oil into the peritoneum (body cavity) of all three fish species. The study aimed to help determine what range of possible responses could occur with oil exposure high enough to significantly affect fish health. The second study investigated the effects of oil-contaminated feed on red drum. The goal was to evaluate how eating contaminated prey might affect fish health. The team is evaluating impacts on specific types of tissues, fluids and the genetic material in cells, DNA and RNA. For instance, bile from fish livers can help reveal possible oil exposure levels and RNA molecules can help reveal the activity of genes involved in immune-system health.

“We’re a step closer to knowing what biomarkers — what subtle health signals — we should look at to diagnose the impacts of oil exposure in wild fish,” Wetzel said. “Our preliminary tests are helping us understand which changes we should look for in the next round of larger lab studies with our fish. We’ve started narrowing down the important signals. Some people are surprised that scientists did not have the opportunity to investigate some of these basic health questions in Gulf fishes before the Deepwater Horizon spill. This oil spill is a tragedy, but we are all making the most of the opportunities it has presented to better understand the health of fishes and our Gulf.”

Using results from 2015, Mote researchers have begun focusing on the subtler impacts of oil exposure in the lab this year, with the ultimate goal of using detailed lab data to help “decode” results from wild fish.

In 2016, Mote scientists and C-IMAGE II partners will conduct a series of multifaceted studies to recreate possible oil-exposure scenarios for all three Gulf of Mexico fish species. Mote scientists began lab work for the effort this month, April 2016.

The goal is to better understand sub-lethal effects that could possibly result from an oil spill. Sub-lethal effects do not kill animals outright but affect their health in subtler ways that can ultimately harm wild populations. These effects are largely unknown for fish exposed to Deepwater Horizon oil. During the 2016 studies, researchers will investigate how efficiently red drum take up and eliminate oil in their environment and how that may impact their potential for recovery after an exposure. The researchers will also conduct a comprehensive reproductive impairment study with Florida pompano, examining how oil affects this species’ ability to successfully reproduce and whether effects are passed from parents to offspring. Finally, researchers will examine the impact of oil-contaminated food and sediments on the adult red drum and southern flounder.

*Findings and conclusions in Mote’s NRDA research are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of NOAA or of any other natural resource Trustee for the BP/Deepwater Horizon NRDA.

—

Founded in 1955, Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium celebrated its 60thyear as an independent, nonprofit 501(c)3 research organization in 2015. Mote’s beginnings date back six decades to the passion of a single researcher, Dr. Eugenie Clark, her partnership with the community and philanthropic support, first of the Vanderbilt family and later of the William R. Mote family.

Today, Mote is based in Sarasota, Fla. with field stations in eastern Sarasota County and the Florida Keys and Mote scientists conduct research on the oceans surrounding all seven of the Earth’s continents.

Mote’s 25 research programs are dedicated to today’s research for tomorrow’s oceans, with an emphasis on world-class research relevant to the conservation and sustainability of our marine resources. Mote’s vision also includes positively impacting public policy through science-based outreach and education. Showcasing this research is Mote Aquarium, open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. 365 days a year. Learn more at mote.org.

Contact Us:

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Fla., 34236. 941.388.4441

Copyright©2015 Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, All rights reserved.