Mote Marine Laboratory celebrated the life and legacy of its founding “Shark Lady,” Dr. Eugenie Clark, during a special memorial event Monday, May 4 — Clark’s birthday — at Mote in Sarasota, Fla.

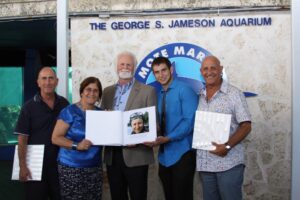

The public celebration and an invitation-only gathering later that evening brought together 550 of Clark’s family members, friends, colleagues and others inspired by her passion for marine science and the oceans.

Clark passed away at age 92 on Feb. 25. Her career spanned nearly 75 years of groundbreaking marine research focused on sharks and other fishes, along with teaching, writing and outreach that touched countless lives and helped people around the world become more ocean literate. Clark is survived by her four children: Hera, Aya, Tak and Niki Konstantinou, and her grandson, Eli Weiss.

Read Mote’s feature story about Clark’s life and legacy.

Clark, an ichthyologist, was a world authority on fishes — particularly sharks and tropical sand fishes. A courageous diver and explorer, Clark conducted 72 submersible dives as deep as 12,000 feet and led over 200 field research expeditions to the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba, Caribbean, Mexico, Japan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, Indonesia and Borneo to study sand fishes, whale sharks, deep sea sharks and spotted oceanic triggerfish. She wrote three books and more than 175 articles, including research publications in leading peer-reviewed journals such as Science and a dozen popular stories in National Geographic magazine.

In 1955, Clark started the one-room Cape Haze Marine Laboratory in Placida, Fla., with her fisherman assistant and with philanthropic support and hearty encouragement from the Vanderbilt family. The Lab thrived in partnership with its community and became Mote Marine Laboratory in 1967 to honor major benefactor William R. Mote. Today the Lab is based on City Island, Sarasota, and it hosts 24 diverse marine research and conservation programs, education programs for all ages and a major public Aquarium. The Lab has six campuses in Florida and more than 200 staff, including scientists who work in oceans surrounding all seven continents.

Clark joined the Zoology faculty at the University of Maryland in 1968, and she officially retired in 1992. She returned to Mote in 2000 as Senior Scientist and Director Emerita and later became a Trustee. There, she continued to build upon and champion the groundbreaking research that she started 60 years ago.

During Monday’s ceremony, it was clearer than ever that Dr. Clark’s legacy is her passion for marine science and her amazing ability to communicate her discoveries to any audience — especially to younger generations.

“Genie was truly a remarkable person,” said Dr. Michael P. Crosby, President & CEO of Mote, during the ceremony. “Her passion for marine science will always be carried on here, in our hearts. Genie had the freedom to pursue her fascination with marine science and the oceans, and she gave birth to Mote, this amazing institution where the next generation of marine scientists will be able to follow in the wave of her legacy.”

“If I had to pick one thing that’s a legacy for her, it’s that she connected with our communities, connected with our young people, and she impressed upon me that we needed to have more young people involved here,” said Dr. Kumar Mahadevan, the President Emeritus of Mote who has known Clark for 37 years. “She helped a lot of generations get inspired about marine science, but also about our coastal environment. That is even more important — we live in a finite world and we need to preserve and conserve what we have.”

Clark led her amazing life “against all odds,” said Dr. Jose Castro, a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who is writing her biography. He noted that Clark, born in 1922 in New York to a Japanese mother and American father, had to overcome discrimination against her heritage, especially around the time of World War II. She also faced gender discrimination from those who believed science was a men’s field. But she succeeded anyway, working with excellent mentors and driven by extraordinary curiosity. “Curiosity is the main quality that distinguishes a good scientist from a mediocre one. She had a lot of it.”

During Mote’s video tribute at the ceremony, Clark’s own words showed how curiosity and determination drove her onward.

“I read about William Beebe, who was of course a great explorer, and I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful to go down (into the sea) like William Beebe?’ My parents would say, ‘Well maybe you can study typing and how to be a good secretary and become a secretary to someone like William Beebe — that would be exciting, wouldn’t it?’ And I would say, ‘No, I don’t want to be a secretary — I want to do that stuff myself. I want to be like William Beebe.’”

Clark got her wish. She will forever have a special place among legendary scientists, said University of Maryland Provost Mary Ann Rankin.

“She is one of these folks like E.O. Wilson, even Darwin — these extraordinary observers, real naturalists in the biological world who really changed the world by their work and their way of seeing a whole area of behavior or species in a different way.”

In the very early days of Mote Marine Lab, Clark was the first to show that sharks could learn through training. In general, she was the first to study the behavior of large sharks experimentally in a lab.

Even before that, she studied fishes in the South Pacific, along with the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba — areas that are crucial to Mote’s research today. Her adventures captivated young people who would later become famous marine scientists too.

World-famous oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Earle wrote a love letter to Clark for Monday’s ceremony.

Earle wrote: “As a birthday present in 1953, my parents gave me your account of traveling alone as a young field scientist in the 1940s under circumstances daunting for anyone of any age or gender at any time or place, exploring reefs among islands in the South Pacific, and the Red Sea, of diving with the legendary fisherman, Siakong in Palau, of your challenges as you emerged as a successful professional scientist, gracefully combining marriage and your passion for ocean exploration.

“For me, it was love at first sight, though a year went by before I actually met you in your trailer-lab at Cape Haze, the true birthplace of what has become the phenomenally successful Mote Marine Laboratory.

“Your life has become intricately and permanently linked to mine and to that of generations of people who have come and will in the future come to know you as a treasured spirit of the sea.”

Clark’s impact on future generations shone most brightly when her only grandson, Eli Weiss, stepped to the podium and shared stories from his days with “Granny Genie.”

He joined her to study the convict fish — one of the species that fascinated her most — when he was a youth who had received his dive certification just a year before. “We dived side by side, studied the fish in the ocean,” Weiss said. “We set up stakes around where they were living, their habitats.”

“It was exciting to get to be there and do that with her.”

He recalled how, in her ‘80s, Clark was still showing the energy and courage that made her special. “We went to a local swimming pool. She was swimming laps and there was a really tall high dive. She got done with her laps, got out of the pool, climbed all the way to the top and dove in — at 80-something years old. The lifeguards all came running and jumped in. They didn’t know who she was.”

Had they known, they might have shown less surprise. Clark was diving in the oceans into her 92nd year. She passed away before reaching her 93rd birthday, but was ultimately re-united with the sea. On March 2, Clark’s family placed her ashes into the Gulf of Mexico from aboard Mote’s research vessel Eugenie Clark.

Remembering that day, Weiss said: “I hope you enjoy your last dive, Granny Genie.”

In lieu of flowers, the public can honor Dr. Clark’s life by supporting her Lab through the Dr. Eugenie Clark Memorial Research Endowment Fund.