Mote Annual Reports

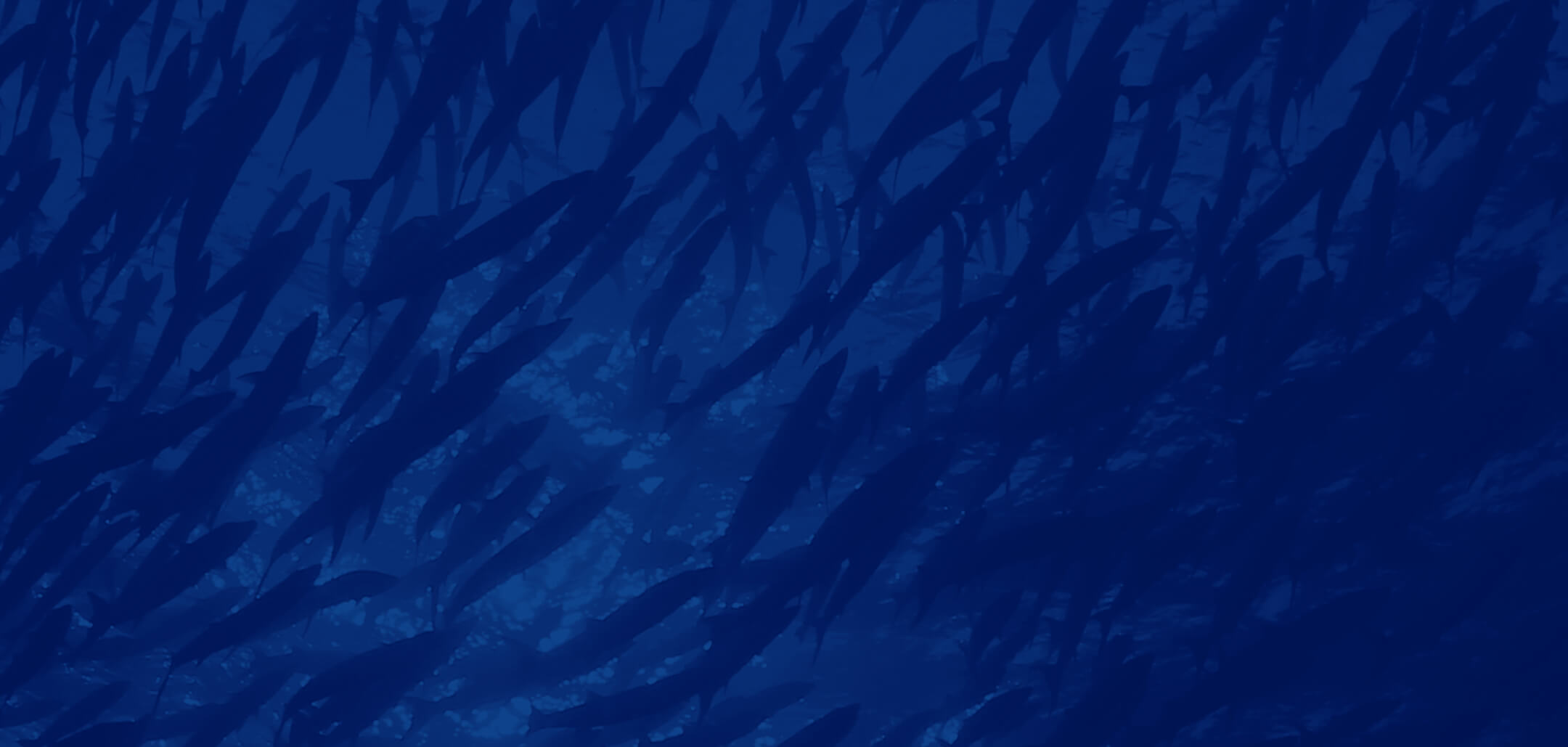

In this year’s report, discover: Mote’s resilient recovery after the hurricane season; groundbreaking innovations leading the charge against Florida’s marine stressors; exciting advancements in our pioneering research to restore seagrasses; how Mote is empowering students to transition from education to careers in marine STEM; our ongoing efforts to protect Florida’s coral reefs; and other remarkable achievements made possible by the unwavering support of our community from October 2023 through September 2024.